The New York Post chats with Pong’s creator Allan Alcorn about its development and success.

An electronic-engineering graduate of the University of California, Berkeley, had paid his way through college by working as a TV repairman before taking a job at Ampex, a large engineering firm in Redwood City, Calif.

That’s where he met Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney, the duo who would go on to form Atari. They recruited Alcorn, then 24 in June 1972, making him he became the company’s third employee. (He still has his worker badge, with the employee number 003, to prove it.)

“We had no money, no manufacturing capacity, no nothing. But I just thought, ‘I’ll go along with it until it blows up,’” said Alcorn, who was paid $250 a week. “It sounded like it might be fun.”

It was low-budget to the point of being a one-man operation.

“People ask me ‘who did the sound on Pong?’ I did. Or ‘who did the graphics on Pong?’ I did,” he said. “Back then it was just me, left to my own devices for two months and there was Pong at the end of it.”

Next stop was Andy Capp’s Tavern, one of the Atari team’s local bars in Sunnyvale, Calif. — about 10 minutes from the town of Cupertino, the future home of Apple’s headquarters. Alcorn left the game between a pinball machine and a jukebox and waited. “I just wanted to see if anybody would play the darn thing,” he recalled.

A few days later, the bar owner called the Atari office. Pong had gone wrong.

“It didn’t surprise me it was broken because it wasn’t built to last,” said Alcorn, who went to the bar to check it out.

The following day, he swung by Nolan Bushnell’s office and dumped a large bag of quarters on his desk. “I said: ‘I found the problem — the goddamn thing’s making too much money,” he recalled. The coin collector was full.

Soon after, the first run of 12 coin-operated Pong machines was installed in bars across California. They cost $500 to make and Atari was selling them for $1,000 cash upfront. The business grew quickly and even spread overseas.

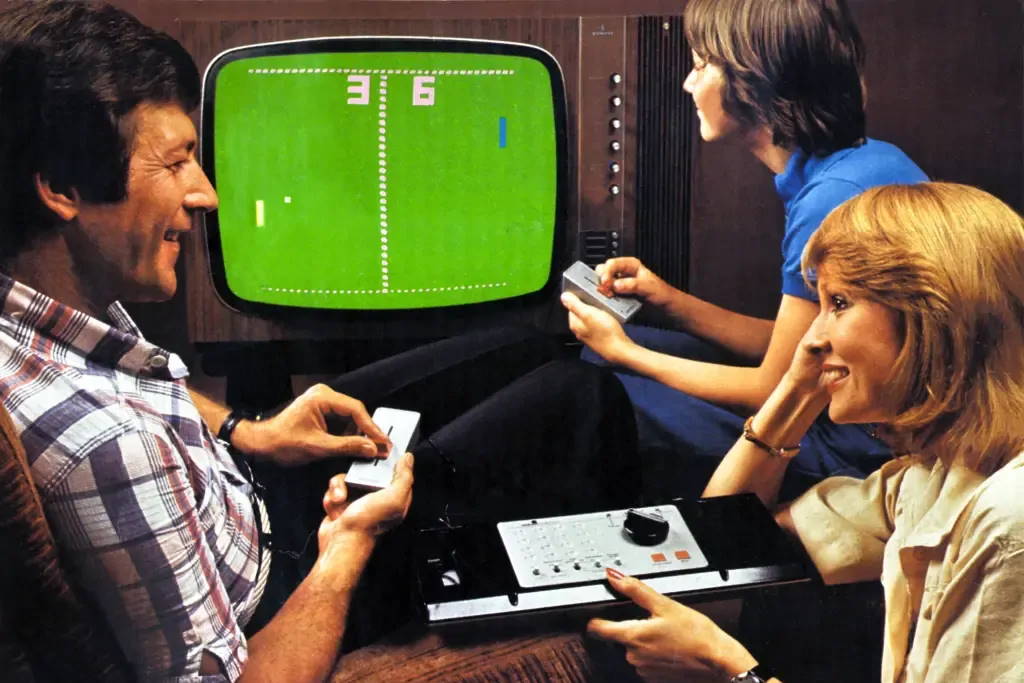

By 1975, the company was selling a home console version of Pong — and its speedy success put Atari on the radar of some much bigger companies.

In 1985, he was appointed an Apple Fellow by Steve Jobs, for his work in digital video compression.

“I didn’t really want to work for the guy. He could be a real nasty guy to work for,” he said. “But it sounded interesting and, you know, it was Apple.”

One of the last things he worked on at Apple was a project compressing video to become datatype, making it smaller and more versatile.“Little did I know that it would end up filling the internet full of puppy and cat videos,” he said.

Now retired, Alcorn’s ingenuity is rightly recognized for the part it played in creating the global video game industry we know today.

Gavin Newsham – New York Post