A look at the life of Andrew Smith Hallidie, inventor of the San Francisco cable cars from the Cable Car Museum website.

His early training was of a scientific and mechanical character, and at ten years of age he successfully constructed an “electrical machine.” When he was thirteen he began work in a machine shop and drawing office operated by his brother, and there gained the practical experience that stood him in good service during the remainder of his life. In the evenings he continued his studies, but manual labor during the day and study at night began to undermine his health, so his father decided to take him to California. His father was interested in the Frémont estate in Mariposa County where he thought the prospects for financial reward were extremely bright.

In 1867 Hallidie took out his first patent for the invention of a rigid suspension bridge, and in the years thereafter he took out numerous patents for his inventions. Among these was the “Hallidie Ropeway [or Tramway],” a method of transporting ore and other material across mountainous districts by means of an elevated, endless traveling line, which he had invented in 1867.

in 1870, a statement is there published in its telegraphic news of what I proposed to do, viz: to run a rope railway to carry passengers from the city to the plateau above.

At that time Hallidie had successfully installed a number of rope-ways in the mining districts of California. Great iron buckets containing rock and ore were carried across deep chasms and up precipitous mountain sides, where it was impossible to build bridges or roads. He undertook to adapt the same system to the propulsion of street cars up the hills of the city. The enterprise called for an endless wire rope, underground, to which a car could be attached, and from which it could be released at will.

In 1871, he completed plans by which street cars could be propelled by underground cables. In a report to the Mechanics’ Institute he tells of the inception of the idea: “I was largely induced to think over the matter from seeing the difficulty and pain the horses experienced in hauling the cars up Jackson Street, from Kearny to Stockton Street, on which street four or five horses were needed for the purpose–the driving being accompanied by the free use of the whip and voice, and occasionally by the horses falling and being dragged down the hill on their sides, by the car loaded with passengers sliding on its track…..”

The next step was to secure the necessary capital for a demonstration. Discouragement only served to make Hallidie more determined.

During the following twelve months Hallidie succeeded in interesting three men, the only ones among his friends and business associates who could be induced to help. Even they were dubious about the feasibility of the project and were induced to participate under the pressure of a strong friendship.

The cable railway was constructed from the intersection of Clay and Kearny Streets to the crest of the hill, a distance of 2,800 feet, making a rise of 307 feet.Accordingly, a franchise was obtained, a new survey made, and subscriptions to purchase stock were invited. The public responded only to the extent of one hundred and twenty shares. Even those few shares were soon turned back to the company, so great was the force of unfavorable public opinion, concurred in by the best engineering talent in the West.

Periodical newspapers, of discouragement seized the three men. Hallidie would spent hours using convincing arguments to show that the plan would actually work. A circular was issued carefully describing the project. An office was taken in the Clay Street Bank Building, and a working model was placed on exhibition. Finally, by persistent solicitation through canvassers among the property owners on the hill, pledges totaling $40,000 were obtained, to be paid upon completion of the undertaking.

However, pledgors to the total of only $28,000 met their obligations. Hallidie himself contributed $20,000, all he had, and his three friends, about $40,000. An additional $30,000 was obtained (through Mr. Burr, of the Clay Street Bank) by a ten-year loan bearing ten per cent interest–a mortgage on the property being given as security.The first day of August 1873 was approaching. If on that date no cable car was running, all rights would expire and everything would be lost.

Desperate efforts to complete the building of the cable road were made, and at a little past the midnight hour Of July 31, a few tired, nervous men met at the power house located at the corner of Leavenworth and Clay Streets. All night, with feverish anxiety, they had been watching the hurried efforts of the workmen.

Within the power house, furnace fires roared under the boilers which were blowing off their overload of hissing steam which seemed to be angered at being harnessed to do such unaccustomed work. At last, all was ready. The engine started, very slowly at first, and as the tension took up the slack of the several thousand feet of cable, the steady hum was heard of the endless rope in its long tube under the surface of the street. The grip car was put in place. The brakes, crude, straight levers pressing on the wheels, were applied and found to be effective.

The final moment of success or failure had arrived. At five o’clock in the morning on August 1, 1873, the group, consisting of Hallidie and his associates, stood at the top of the Clay Street hill at the Jones Street crossing.

Day was breaking. A dense fog was coming through the Golden Gate and was rolling over Nob and Russian hills. The bottom of the steep Clay Street grade was obscured by the early morning mist. From the open slot near the middle of the street came a mysterious rattle. Hallidie listened intently, nodded with an air of satisfaction and ordered, “All aboard.”

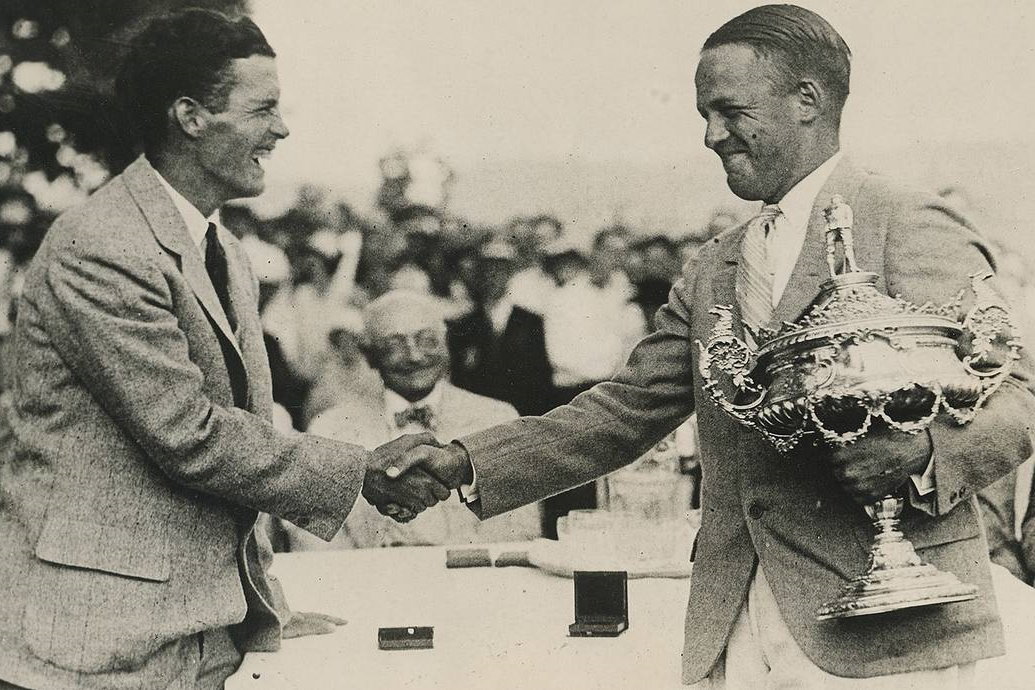

The workmen next pushed the car forward to the brow of the hill at Jones Street where the slot and tube commenced and adjusted the curiously shaped grip wheel. The grip, which was Hallidie’s invention, moved up and down by means of a screw and nut on a hand wheel, and fastened its jaws securely to the cable. Hallidie, assuring his friends not to become uneasy as there was no cause for alarm, sprang to the levers; instantly the car and its human freight dropped out of sight into the mist below.The successful test was accepted soberly. It was a solemn affair and only a round of silent hand shaking gave expression to the men’s feelings. The town was asleep. An enthusiastic Frenchman thrust his nightcapped head out of a window as the car went by and threw a faded bouquet. His was the only demonstration.

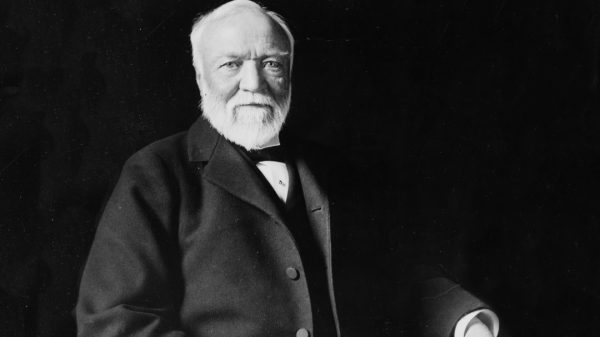

Hallidie lived to see the fruition of his many years of strenuous efforts. Cable railroads spread to Oakland, Los Angeles, Kansas City, Chicago, St. Louis, Philadelphia, New York, London, and Sidney. Many of his inventions were used, and the collection of large royalties for a long period made him wealthy.Andrew Smith Hallidie By Edgar Myron Kahn

Hallidie deservedly took his place among San Francisco’s honored citizens and devoted much of his time to the general welfare of the community. In a reminiscent mood, Hallidie commented: “California that has become so endeared to me was an accidental love, and brought about by circumstances over which I had no control.”