Richard Koch explores how Walt Disney funded his dreams for Huffpost:

Third, and perhaps most surprisingly, the Disney Company, unlike most movie studios, decided to treat the emergence of television not as a threat, but as an opportunity. In the early 1950s, however, this was more an aspiration, and negotiations with the ABC network were tortuous.

It was with all this on the company’s plate that Walt, at the then-advanced age of 51 – and although he didn’t know it, only a decade or so from his death – got a bee in his bonnet about a further detour in his empire, the idea of building a huge and unprecedented leisure park. This seemed to Roy and other directors to be a complete diversification move, and one which, if the company went down that road on top of its other bold new ventures, could sink it entirely.

The costs – relative to the firm’s immediate cash and prospects – were astronomical. A Disney movie at the time might cost between $1m and $2m – which was already huge relative to the firm’s profits, not all of which converted into cash. The Disney Company was already stretched to the limit by its three new film-making ventures. Yet it was calculated that Disneyland would cost between $10m and $20m to create. Surely no board in its right mind would allow its CEO to go down that road.

Well, the Disney Board quite understandably did not want it to happen. Roy Disney led the opposition. Their doubts were thoroughly reinforced by the initial market research. Every industry expert said that no amusement park could run without the thrills and spills of traditional rides – yet Walt was adamant that they would find no place in the park of his imagination. Roy thought that Walt had taken leave of his senses.

Walt’s response was to set up a new company named by his initials, WED Enterprises, to develop the park. This was not in order to raise money, but to develop the idea for Disneyland with a small group of like-minded people hand-picked by Walt. The truth is, he had been in despair for years, feeling that he had lost control of the studio, as it had morphed into a big corporation.

Now Walt felt entirely re-energized, happy in his new sandbox. The small community of WED allowed him to give free rein to his imagination and encourage his team to do likewise. One of his colleagues said Walt enjoyed himself so much “because once again he owned WED as he once owned the Studio, before it went public … at WED you no longer had any big departments to deal with … it was fun just to get back into that small scale again.”

While he planned Disneyland, Walt paid little heed as to how he was going to pay for it.

He provided what we would now call seed capital to WED, borrowing $50,000 – “the limit of my personal borrowing ability” – from his bank against the security of his life insurance policy. “My wife,” he told a reporter, “keeps complaining that if anything happened to me, I would have spent all her money.”

Walt knew that if Disneyland didn’t work, he might face bankruptcy. He sold his newly-acquired second home because he needed the money for the park, and he put his remaining home into his wife’s name.

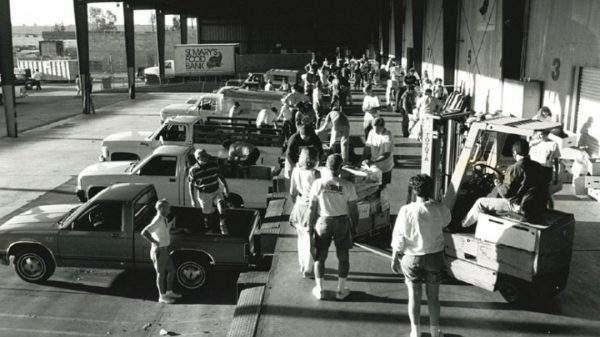

Once the site had been identified – a huge orchard, 160 acres in Anaheim, which was the largest source of Valencia oranges in America – Disney had to focus on raising the money to build the park. He did this through a stroke of genius – marketing the idea of Disneyland to the television networks and attempting to get them to fund the park in exchange for Walt Disney Productions (the Studio) agreeing to make a series of movies specifically for television. There was one problem – the major networks all rejected the idea. But Walt kept going, and eventually persuaded ABC-Paramount to bite.How Walt Disney Funded His Dream, Richard Kock

At this stage, Roy Disney, who had threatened legal action if Disneyland used any of the Disney characters or the Disney name – both of which Walt viewed as essential for the park – came on board, partly because of the television deal Walt had negotiated, and partly because of a phone call from a banker Walt had approached for a loan. Roy fully expected the banker to say that the project was hare-brained. “We went over the plans,” the banker said to Roy. And what did the banker think of it? “You know, Roy,” he said after a dramatic pause, “that park is a wonderful idea!” Roy later said, “At that, I nearly fell out of my chair.”